Why does the Sap Flow?

Behind Embark Maple is a small family farm, run by a small Wisconsin family, that seeks to celebrate connection to our natural world. In 2011 we set sail on an unknown adventure in maple farming, cultivating a perennial relationship with the forest we call home.

The winter of 2025 was filled with mixed emotions, a high of which was optimism for the upcoming maple season. Being observant folks, we’ve picked up on the trends of warmer winters & earlier springs leading to more volatile maple seasons, so we did our darnedest to be ready for it! This season we started tapping our trees extra early, and with the help of a couple friends we had 4200 taps-in-trees by the end of February, not missing a drop of sap.

The month of March brought solid frost depth, desirable temperature fluctuations, and sapflow commencing on a schedule more close to “normal” than we’ve experienced in a while. The sap started flowing into our tanks over the first couple weeks, cumulating to a few thousand gallons. Bree boiled down our first barrel of syrup on March 17, slightly delayed due to some emergency evaporator welding. What struck us was that the sap flows never really “took off” like past seasons. Looking around the woods, it didn’t take much imagination to start speculating what was influencing the trees.

Before every season folks ask us if we think we’ll have a good year. With Bree and I both being data nerds, we seek out any signs and information to help us better understand the maple season. One particular variable I’ve been interested in is frost depth, as frozen-solid ground can help temper early warmups experienced in the forest, and possibly prolong the maple season. I found a local frost gauge managed by the county highway department, and began digging into the data to see if it would correlate to our experiences and observations.

In 2024 the maximum frost depth at the Coon Valley location (nearest our farm) was 11” recorded on Jan 23, and by February 2 all the frost observed in the ground was gone. 2024 presented the earliest maple season we ever experienced, with sap flow beginning late January and concluding at the end of February. This winter I eagerly watched the frost depth observations grow to around 36” of frost when the sap started flowing in late February, and was feeling pretty good!

What makes the Sap Flow?

Maple sap provides energy to the forming buds before the tree can sustain itself via photosynthesis. This energy takes the form of carbohydrates and sugars stored in the various tree rings from past growing seasons, and is transferred in water via internal cell pressure, all the way from the roots of the tree to far reaching branches. When days are above freezing, there is a small positive pressure in the tree and the sap flows upward (and outward), when the temperature dips below freezing the internal pressure drops to protect the developing buds. This cycle ideally repeats itself over a couple months for a really good season, but can be as short as a week in poor year.

Much of Wisconsin experienced severe drought in 2023, followed by a very warm & dry winter. Our region of Wisconsin experienced a second year of drought in 2024, again followed by a dry winter with little to no snowpack. Maple trees photosynthetically fix carbon (ala carbohydrates/sugars) when CO2 is absorbed by leaf stomata. During periods of low soil moisture, these stomata can close, reducing the amount of sugars stored in the growth ring during that growing season. Additionally, the fibrous root hairs responsible for uptake of soil moisture can dry out, again limiting the ability of the maple tree to produce sugar. Fortunately, the beautiful thing about perennials is that they tend to be more resilient to weather anomalies. Maple sap can contain sugars from 20-30 growth rings, with the outer most rings being the most productive.

Unsurprisingly, one of the most significant aspects of sap flow is the water itself. If soil moisture is low due to prolonged drought, and there is little snow melt or rain providing water to the trees during the maple season, sap flow can be dramatically reduced. Even though we experienced perfect temperature fluctuations with relatively deep frost, the lack of soil moisture available caused the sap to simply stop flowing right in the middle of the season. We measured sugar content, and it was about 25% higher than average, coming in at 2.5% sugar-by-mass as compared with a more typical 2.0%. This might possibly suggest the trees were at least healthy enough the previous growing season to produce sugar, but just didn’t have the moisture to make sap during the season. Our harvest was only 25% of an average year.

Sometimes it feels like we’re just at the whim of ever changing weather patterns, with nothing we can do but sit back and take it. Our lives and livelihood depend on harvesting maple sap, so that’s not really an option for us. More of our annual precipitation is falling in a shorter period of time, decreasing opportunity for water to infiltrate the soil. After a series of flash floods ravaged through our farm in 2016, 2017, and then culminating in mass destruction in 2018 after 13 inches of rain fell overnight, a small group of rural neighbors got together to do something. This wasn’t the first time the community came together to do something often called “too big to change.” In the 1930s many local farms were quickly becoming financially insolvent due to massive soil erosion that resulted from implementing traditional Norwegian farming practices, namely plowing straight up and down the hillsides. The Soil Conservation Service (now Natural Resources Conservation Service) partnered with local farmers one-on-one to identify and implement farming practices that would reduce soil erosion and runoff, such as farming along the contour (parallel to the hillsides), which also dramatically improved their profitability. Over about a decade most of the farms in the region adopted these same practices, some of which remain in place today.

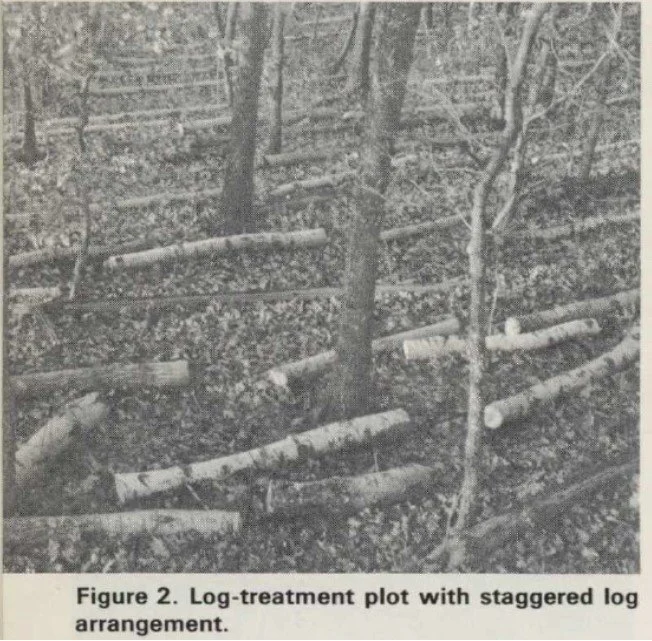

Simple Practices Along Forest Edge Reduce Upland Runoff - Curtis, Journal of Soil & Water Conservation, 1967

At first glance, what does flooding resilience have to do with drought? The obvious answer is water, but digging a little deeper it’s really about infiltration. Continuing the conservation work done locally in the 1930s, the Coulee Experimental Forest, located about 15 miles from our farm, has conducted long-term forest-watershed research to develop conservation practices unique to the highly erodible lands in the Driftless area. Many of the practices studied in the 1960s are still not only visible, but actually functioning to decrease water runoff from ridgetop fields, and infiltrating that water through the wooded hillsides. Simple practices, such as strategically laying logs horizontally across the hillsides above gullies and ravines, act like micro-terraces slowing the water down and providing it time to soak into the soil like a sponge, recharging the local water table. While many of these practices were identified, they never gained widespread adoption outside of research plots.

Here we are, almost 100 years after the nation’s first watershed scale conservation project, trying to solve a very similar problem but with some new variables. The meeting of neighbors wanting to do something about flooding has grown into the Coon Creek Community Watershed Council of which Eric is a board member. We recently held our Coon Creek Confluence event, bringing together over 800 people to celebrate & promote watershed literacy. The same practices that could help reduce destructive flash flooding could also benefit our forest during years of drought. The sap flow is for more than just making maple syrup, its our connection to our community, past, present & future.